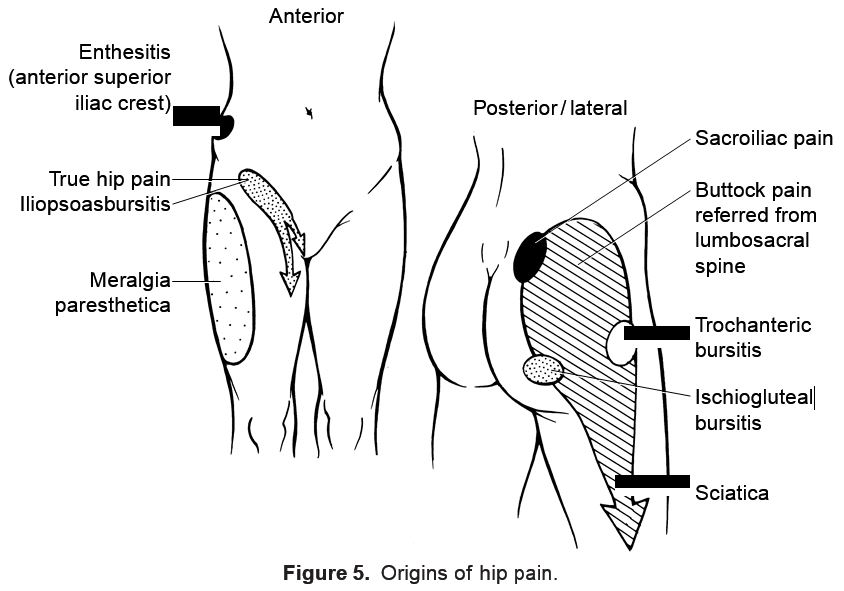

Definition: Hip pain is one of the most often misdiagnosed joint complaints, primarily because of the public misconception that the hip is located in either the gluteal or trochanteric region. True hip pain is sensed anteriorly and may radiate medially into the groin or to the anteromedial thigh. This is to be distinguished from the more common complaint of buttock pain that is often referred from the lumbosacral impingement of nerve roots. Trochanteric pain is sensed over the upper lateral thigh with point tenderness and usually indicates trochanteric bursitis (Fig. 5).

Anatomic Considerations: Hip pain may originate in the femoral-acetabular joint or joint capsule, proximal femur or acetabulum, pelvic rami, surrounding bursae (e.g., trochanteric, ischiogluteal, iliopsoas), ligaments (e.g., inguinal, il-iofemoral), and intraabdominal or vascular structures.

Etiology: Pain in the hip may result from traumatic, mechanical/degenerative, inflammatory, reactive, infectious, or neoplastic disorders affecting the joint or juxtaarticular structures.

Cardinal Findings: In elderly individuals, hip pain is commonly caused by OA of the hip, referred lumbosacral pain, trochanteric bursitis, or osteoporotic fractures. Young and middle-aged adults are often affected by trochanteric bursitis, adductor tendinitis, or inflammatory arthritis (e.g., RA, reactive arthritis). Hip pain in children is commonly caused by toxic synovitis of the hip, juvenile arthritis, or congenital anomalies of the joint. Toxic synovitis of the hip is common in children 1 to 13 years of age and typically follows an upper respiratory infection. It manifests as an acute inflammatory arthropathy that is self-limiting and lasts 2 to 4 weeks. This condition responds well to rest and aspirin or NSAID therapy.

Referred pain accounts for many cases of hip pain. Whereas involvement of the T12–L1 nerve roots may result in buttock/trochanteric pain, L2-4 nerve roots may produce inguinal or anterior thigh pain (see Dermatomal Map). Thus, it is important to detect lumbosacral spine, vascular, or intraabdominal disorders that may masquerade as hip pain. Buttock pain may originate from the lumbosacral spine, sacroiliac joint, ischiogluteal bursa, or vascular insufficiency. Groin pain may be from true hip disease, iliopsoas bursitis, hernia, adductor tendinitis, pelvic fracture, osteitis pubis, ureteral stones, or pain referred from L2-4 nerve roots.

Trochanteric bursitis manifests as lateral thigh pain, often with radiation downward to the knee. It is worsened by general activity, sleeping on the affected side, or sitting with the affected leg crossed.

Ischiogluteal bursitis will manifest as lower buttock pain, possibly with radiation down the leg. Pain is worsened by prolonged sitting with legs uncrossed and may be exacerbated by standing on tiptoes.

The iliopsoas bursa lies between the psoas muscle and hip joint capsule. Inflammation of the psoas bursa may manifest as pain in the groin or anterior thigh that is exacerbated by extension of the hip or flexion against resistance. Patients may hold the joint in flexion to reduce pain. Iliopsoas bursitis is unaffected by rotation.

Acute monarticular presentations should lead the examiner to consider urgent noninflammatory (e.g., fracture) or inflammatory (e.g., septic arthritis) causes. Severe hip pain associated with weight bearing should suggest a fracture.

By virtue of its deep location, inspection and palpation is unlikely to yield diagnostic findings. Examination of periarticular bursae may disclose point tenderness over the greater trochanter laterally or ischial tuberosity posteriorly. Palpation and auscultation should identify abnormal bruits or pulsatile masses involving the abdominal aorta or iliac arteries. Palpable masses over the anterior groin may suggest a hernia or iliopsoas bursitis. Adductor tendinitis is common in young individuals who assume a straddling position (e.g., gymnasts, horse-back riders) and manifests as pain in the groin or anterior thigh. Pain is elicited over the insertion of adductor musculature and is exacerbated by passive abduction or active adduction. Range of motion testing (flexion, internal and external rotation, abduction) may disclose true hip joint involvement because bursitis seldom causes true limitation of motion. True hip (and sacroiliac) disorders and range of motion are best assessed using the Patrick (or Fabere) test (see Evaluation of Musculoskeletal Complaints, Table 7). Notably, nondisplaced fractures may demonstrate a normal range of motion until extremes in rotation are achieved. A pelvic tilt may indicate true hip disease, scoliosis, or a leg length discrepancy. Leg length discrepancies may be ascertained by comparative measurements from the anterior superior iliac crest to the lateral malleolus. Normally, there is <1 cm variation between limbs. A flexion contracture of the hip may indicate antecedent trauma or undiagnosed articular inflammation and is best diagnosed by the Thomas test (flexion of the contralateral hip results in involuntary flexion of the involved hip).

Diagnostic Testing: Laboratory testing should be guided by the clinical findings. The examiner should avoid using routine laboratory screening tests. Inflammatory or infectious conditions may be associated with nonspecific elevation of acute-phase reactants (e.g., ESR, CRP). If acute infectious arthritis is suspected, synovial fluid aspiration (under fluoroscopic guidance), culture, and analysis should be strongly considered.

Imaging: For nontraumatic acute presentations, radiographs are not indicated because they are seldom revealing. Those with trauma or who have undiagnosed chronic hip pain should undergo radiography of the hip and pelvis. Lumbosacral spine films should be obtained if there is a history of low back pain, if hip and pelvic radiographs are unrevealing, and if referred lumbosacral pain is suspected. MRI has largely replaced the bone scan in the evaluation of hip disorders and may be useful in the diagnosis of osteonecrosis, osteomyelitis, or early fractures not yet apparent by routine radiography.

Therapy: Depending on the condition, nonpharmacologic modalities of cold or warm compresses, immobilization, ambulatory-assist devices, physical therapy, and range of motion exercises may be indicated. Symptomatic control of pain may be achieved with NSAIDs or simple analgesics (e.g., acetaminophen). In selected instances, judicious use of local corticosteroid injections may be helpful in treating trochanteric or ischiogluteal bursitis. Surgery may be indicated for some pelvic, acetabular, or femoral fractures. Total hip replacement may be indicated in those with advanced joint damage and pain.

| Table 16: Common Causes of Hip Pain |

|---|

| Arthritis |

| Inflammatory: rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthropathy, septic arthritis, juvenile arthritis, toxic synovitis of the hip, sarcoidosis |

| Noninflammatory: osteoarthritis, osteonecrosis, fracture (femur, acetabulum, pelvic rami), hemochromatosis, osteoid osteoma, hemarthrosis |

| Periarticular |

| Inflammatory: septic bursitis, enthesitis, polymyalgia rheumatica, osteomyelitis |

| Noninflammatory: trochanteric bursitis, iliopsoas bursitis, ischiogluteal bursitis, ad- ductor tendinitis |

| Abdominal/genitourinary: aortic aneurysm, hernia, pelvic inflammatory disease, ureteral nephrolithiasis, retroperitoneal disorders, lymphadenopathy (inguinal, paraaortic) |

| Bone: fracture (osteoporotic), Paget disease, osteitis pubis, osteomyelitis, osteoid os- teoma |

| Referred pain: sciatica, degenerative disc disease, lumbar facet osteoarthritis, spinal stenosis, vascular insufficiency, meralgia paresthetica, sacroiliitis |

Adapted from: RheumaKnowledgy

Musings

Avascular Necrosis of Hip March 9, 2017

Pre-Op DMARD Use March 8, 2017

Hip & Knee Surgery March 7, 2017

Predicting OA Progression March 6, 2017

Targeted OA Treatments March 5, 2017