Osteoarthritis is the most common type of joint disease, affecting more than 20 million individuals in the United States alone (see Epidemiology). It represents a heterogeneous group of conditions…

emedicine.medscape.com

Osteoarthritis: time for us all to shift the needle

OA is a highly prevalent, disabling condition that affects approximately one in eight adults worldwide. As the most frequent cause of mobility disability in older adults, and with its high level of cost to healthcare systems, it causes a substantial individual and societal burden [1]. Due to socio-demographic changes in an increasingly aged and obese population, we expect that the prevalence will continue to grow dramatically.

In this context of substantial burden, we recognize that a large proportion of patients with OA are faring badly [2] and the majority are not receiving appropriate care [3]. It is in this context that this thematic issue is both timely and important. This editorial will briefly summarize many of the salient points brought forward by the wonderful authorship team.

With this background of increasing prevalence, dramatic increases in individual and societal burden, and health care systems that are both overwhelmed and fiscally constrained, it is critical that we highlight the epidemiology of OA with a view to potential public health implications. The two dominant risk factors for OA—incidence-obesity and joint injury—are continuing to increase worldwide and are eminently modifiable. The foremost of these, obesity, is an epidemic that has implications for many non-communicable chronic diseases. While we cannot ignore individual responsibility, it will require governmental and organizational support consisting of policy changes in order to promote healthy weight, reduce sedentariness and facilitate large-scale benefits. Following substantial knee trauma, a widespread community problem that tragically typically affects young adults, the majority of individuals will develop OA within 10–15 years. The implications this has for disability, employment and general health are staggering. Injury prevention schemes have been implemented successfully in many progressive nations across multiple sports and should be encouraged and more widely adopted worldwide. Not deploying public health interventions for these eminently preventable risk factors is a major failing in our therapeutic armamentarium [4].

Our understanding of the pathogenesis of OA has advanced dramatically. This is no longer a cartilage-centric disease and archaic terms such as wear and tear and degenerative are now considered both pejorative and inaccurate. OA is best characterized as a disease with chronic abnormal remodelling affecting the entire synovial joint organ with the outcome being structural and functional failure. Historically terms such as osteoarthrosis were used to highlight and differentiate this disease from other inflammatory rheumatic conditions. We now know that inflammation is a key part of this disease and that the ‘itis’ in osteoarthritis is entirely appropriate. In part, this inflammatory change is driven by adipose tissue and the increasing importance and role of fat in this disease cannot be overstated. Similarly, we have known for years that increasing strength through targeting muscle is an important therapeutic tool in our armamentarium. We now have a better understanding of the role of muscle in both the pathogenesis and the management of the disease.

The structural failure of the joint is known as the disease. Its clinical importance derives however from the illness—that is, when a person presents with symptomatic consequences. Typically clinical presentation is driven by pain and is usually the main determinant of health service utilization. The aetiology of pain is complex and the biopsychosocial framework within which this is understood is underpinned by a complex biological entity. Consistent with the complexity involved in the aetiology of pain, we know that the disease (syndrome) is multifaceted and heterogeneous. Increasing research focus is driving meaningful understanding of OA phenotypes that may have important implications for both prognosis and treatment.

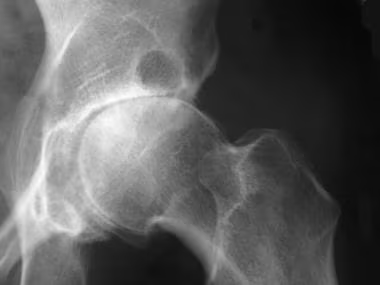

Our understanding of the structural failure inherent in the disease has been vastly enhanced by tremendous improvements in imaging technology and interpretation. This said, it is critically important we understand that the diagnosis of OA is a clinical one and that overuse of imaging can have important implications with regards to excessive health resource utilization and over-treatment. The formulation of a diagnosis and management plan for a person with OA should start with a holistic assessment, rather than a reliance on imaging.

Management of OA is typically not concordant with guidelines as the majority of persons with OA do not receive appropriate care [3]. We underutilize evidence-based lifestyle behaviour management strategies, such as exercise and weight loss [5], in favour of less effective and more expensive treatments. These palliative treatments frequently have no clinically meaningful benefit over placebo, are harmful, are not cost-effective or all of the above [6]. There is robust evidence to suggest many of our commonly used treatments including glucosamine, paracetamol, opioids, viscosupplements and arthroscopy, among others, fall into this category.

It is critical that we engage our patients in a dialogue about what supplements or complimentary therapy they are using. The majority of them are taking one or more, and the most widely used supplements have the best evidence to suggest that they are no better than placebo. Not to denigrate the importance of placebo, but there is promising data from early, albeit poor quality, trials, suggesting some other supplements (including boswellia, curcumin and pycnogenol [7]) may have clinically important effects. Care for patients with OA should be tailored to individual needs and goals. Decision-making should be based on the best evidence with: prioritization of patient safety; accessible information for consumers; and a proactive anticipation of patient needs prioritized over a reactive health service [8]. Our health care systems should encourage enhanced consumer knowledge, self-management and health care delivery characterized by integrated, multidisciplinary chronic disease management. This should entail tailoring management to the individual needs of the consumer, targeted towards the central complaints of pain and functional limitation. This model of health care delivery is supported by many recent policy changes and will facilitate improved patient outcomes while reducing inappropriate health care utilization and resource waste [9].

Ultimately, efficacious treatment for any progressive disorder should also control the factors and forces that drive disease progression. Dramatic advances are occurring in the therapeutic space of symptom and disease modification that will likely portend great benefits for our patients within the next few years.

Persistent limiting symptoms in the face of optimal non-surgical treatment may indicate the need for surgical intervention. It is critically important that a shared decision be made with the patient about whether he or she is a good candidate for surgery and at what stage in the disease course joint replacement be considered.

It has been a pleasure working on this thematic issue with my friends and colleagues and I thank them for their valuable contributions. I am sure that you will see upon reading this issue that it reflects tremendous insight and a great overview of this complex and developing disease.

academic.oup.com

ard.bmj.com